Your cast is the story. The story is your cast. These are not separate entities, and if you fail to deliver a strong, compelling cast, then your grand imaginings will be as flat as day old soda.

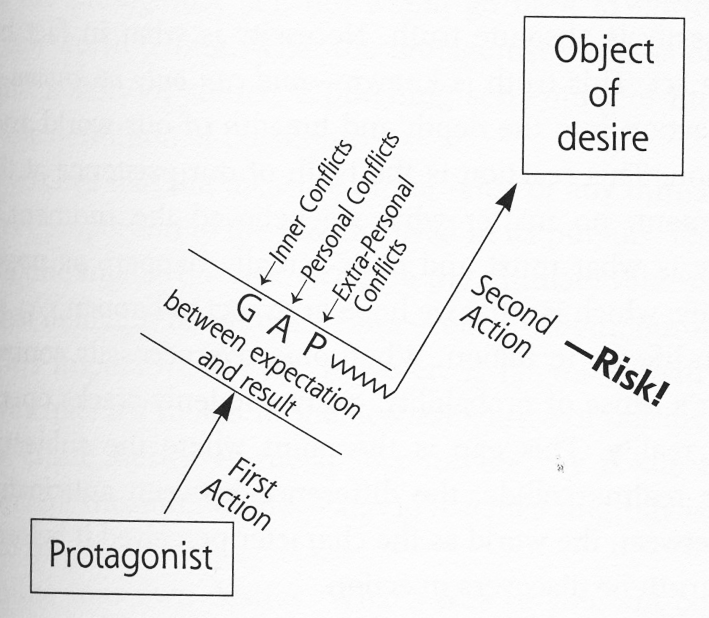

A story follows a meaningful flow. The protagonist, our player as avatar, takes an action, and she expects a particular result from her action: she sees a lever, and she expects pulling it will open the door. The world reacts: a trap door opens under her feet! It reacts differently than we expect, and suddenly things are interesting.

This is called the Gap, and it defines the difference between what the protagonist expects and what is created, in reality, by the antagonistic forces of the story. Without this Gap we have no Story, for if everything happens as we expect, then why are we watching/playing it? How boring would it be to have every lever just open the door as we expect, to have every monster die in one hit. We need this Gap, we need conflict.

“Nothing moves forward in a story except through conflict.” – Robert McKee

We create conflict, the Gap, through the environment, though the mechanics, and through the cast. However, being a simple, fleshy, moving barrier to the player’s progress is empty — gapless — for it’s not the kind of enemy that enhances the story. This is why we give our enemies a trick, and why it is such a painfully important question of your cast: “what’s this guy’s trick?”

In short, you need to define the Gap.

Defining The Gap – Tricks

All combat can be broken down to three steps: action, reaction, and result. I take some action, this may cause one or more different reactions, and this results in one or both of our states changing. You can define everything in this way:

|

|

This is important, because these three parts define how to antagonize our player. When I press a button I expect to perform an action, I expect to cause reactions, and I expect to cause some result. But, as we’ve discussed, things that we expect to happen may not be what actually happens. Kratos swings his blades at the hoplite and he expects to do damage, but what’s this? His blades bounce off the shield. This was unexpected, but interesting.

We can crack reality open and widen the gap by causing any of the three aspects (action, reaction result) to act in a way that the player does not expect. So when searching for a trick this is where you start. The hoplite, for example, has a move where he runs directly at the player and then performs a double slash. While he is running he will tank through lights hits. The player attacks the hoplite expecting, like all enemies up to that point, to make him react, and yet he just runs right through it and smashes the player in the face. Unexpected, a little frustrating, but interesting.

This would be fine, mediocre, if left as it is, because as it is currently designed it does not provide the player with an opportunity to accomplish and overcome. If you want to bring it to the next level, you must allow the player Close the Gap.

Closing The Gap – Mastery

If all we did was conjure antagonistic forces to pester the player, then the game would be an exercise in frustration. Great stories are created when we allow for the protagonist to close the gap through their ingenuity and skill. So let us return, once again, to the Hoplite where, as stated, we have defined the Gap for this creature: he tanks through attacks when he is running, which will be counter to the players expectations. Now our next step is to consider the Turning Point for our player.

In a story, every scene is a chance for the protagonist to turn from the positive to negative or from the negative to the positive, depending on the kind of story you are telling. In the case of a game, though, it is a chance to turn from the unmastered to the mastered, from the unknowledgeable to the knowledgeable. So when determining how to close the gap, determine what you wish for the player to master. In the case of the hoplite the goals are twofold: crush moves are powerful, and throwing is awesome.

Given these goals, when the hoplite is running at the player we should use this as an opportunity to positively enforce those ideas, and that’s exactly what he does. Crush moves — Kratos’s heavy attacks like Square, Square, Triangle — will knock the hoplite out of this rushing attack, and he can, as you would guess, be grabbed right out of the rush. In fact, you can pretty much throw the hoplite all day every day right until he dies. It’s the best tactic to use against him, and goes a long way to showcase the power of the throw.

You can see the power of defining and then closing the Gap. A cast that defies the expectations of the player and then allows them a means to overcome that source of antagonism is going to be the exact kind of cast member that you talk to your friends about. It is the exact kind of cast member that creates stories.

A Short Case Study

Defining the Gap creates stories? I dunno, Mike, that sounds like a bunch of hogwash and hoojaz. I know. Trust me, my friend, you already agree with me. In your experiences, I’m sure, you have had games where you enjoyed fighting things, and games where you were bored to tears with every fight. You simply lacked a word to describe WHY you liked one over the other, because no matter how cool and flashy your player, if he is not challenged by expectation defying forces, then all that flash is for naught.

One of my favorite games, Resident Evil 4, is the king of this. Years of zombie games had us RIPE for that game. See a zombie, shoot the head. That’s just how it works … or so we thought. They didn’t just crack open a gap, no, they exploded it open; by giving us enemies that no only reactively put their hands in front of their faces, but who would dodge out of the way of your gun. These aren’t my father’s zombies! They weren’t even zombies at all.

Better still, they gave us a means to close that Gap. Shooting them in the legs or the feet, made them take a knee; shooting them in the hands made them drop their weapons; and shooting them while they were running (oh my god they are running) made them fall flat on their face. Just about every part of their body was useful. Who doesn’t have at least ONE interesting story about your first run through Resident Evil 4? That is defining the Gap with brilliance.

When Not To Define The Gap

A Gapless enemy is still antagonistic, though; I mean, it’s still trying to kill you, right? It’s still trying to ruin your day, to stand in your way of progress. A gapless enemy, however, is boring, it’s bland. But banality can have its advantages.

The soldiers of City 17 (Half Life 2) are fairly gapless in their design. They are men, they carry guns, they shoot at you, but the game cleverly uses them for the environmental Gaps it creates. Think of the opening sequence where you are running through the city, and at almost every turn they are there, subverting your expectations of where you should go. Brilliant level design that creates story through constantly antagonizing your expectations. You enter a stairwell and it feels natural to head down, but there they are, coming up the stairs, shit go the other way … almost every encounter where they appear is never simply about them. No, they are combined with environmental moments, the level’s story.

That is not all, as they also are used in combat puzzles. See, combat puzzles are tricky, because when you ask people to choose between thinking and fighting, chances are they are going to fight. Therefore you need enemies that are, strange as it seems, a little bland, and I mean this in a functional, expectation defying sense. The soldiers of City 17 are beautifully designed in a visual, auditory, and thematic sense, which goes a long way to making them interesting despite their functional homogeny.

Conclusion

In the end, though, it is the conflict-creating, expectation-defying members of your cast that are going to craft the water cooler moments you dream of creating. It is in those moments, where expectations are defied through forces of antagonism, that great stories are created; therefore, when laying down the structure of your cast, always remember the important question to ask: “what’s this guy’s trick”?