Every move you can think of has already been created.

It sounds ludicrous, but there are only so many ways that one character can beat up another character, and all of that expended effort, all of that struggle to come up with a “cool” new special move, all of that work comes to naught when you end up with something that is, at its core, derivative. That time is better spent on other areas of the game.

Do not be ashamed to use the ideas of other designers. It is no more offensive to use a pre-constructed library in Java, than it is to take the ideas from another game and reapply them. The ideas don’t make the designer, execution does. Throw off these chains of constantly reinventing the wheel and get to stealing borrowing mining. The mining process begins at the greatest source. At the fount of cool, flashy and powerful moves: Marvel vs Capcom 2.

Rides are about to get taken

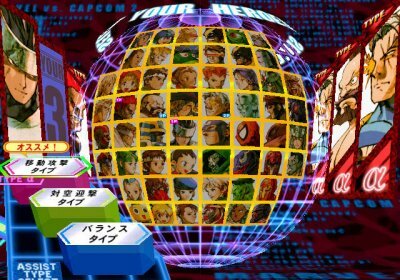

The year is 1998 and Marvel vs Capcom explodes into arcades, and taking the ideas learned from the previous VS titles, it expands them to both the marvel and capcom casts. Two years later, its follow up, Marvel Vs Capcom 2 (MvC2), was the pièce de résistance. It used all the wonderful ideas of simplicity, massive fan service, team attacks, and bad-ass moves laid down by its predecessors, refined those ideas, and then coupled them with a dizzying cast of character. Do the math and you quickly see why this game is a treasure trove of ideas. 56 characters in total, each with several normal attacks, air attacks, special moves, assist moves, hyper moves… it quickly adds up.

The quantity of moves is not the only reason MvC2 is an inspiration. The design philosophy of this game, of the VS series in general, is that if you “break” everyone, everyone is balanced. Too often, when things seem overpowered, our instincts tell us to swing that “nerfbat” like the game owes us money, but if you are going to make a move impotent, then why even have the move? It’s true that in MvC2 not every single move, of every single character, is a game-breaking super attack (that’s just unrealistic). But for each character the designers strove to give each character a “trick” – something fun to give them style. Here emerges the beauty and joy of this game. Around every corner is some new eye-exploding, opponent-smashing or health-restoring nugget that is yours to discover, and there is a lot to discover. Yes, many moves are character-themed, subtly-twisted derivatives of other moves, but it still leaves us with a large amount of ideas to mine both thematically and functionally.

Shit’s about to get real

Having a cast of 55 characters means you have a great collage of themes to pull from: plant guys, giant robots, samurai, cyborgs, ninjas, demons, hulks, egyptian gods, juggernauts… the list goes on. When stuck thematically, this game can be an inspirational source. Even if you have a character that doesn’t fit a mold cast by MvC2, the level of creativity can be helpful to get ideas popping.

As a thematic tool MvC2 is great, but what is more beneficial is its help in defining functionality. When designing enemies your goal is to make sure that every guy gets his own little trick. The trick can be something as simple as the pest enemy you use to swarm the player (emphasizing your big area attacks), or it can be something as special case as the medusa from god of war (emphasizing movement and timing your attacks).

That’s a lot of characters

As a source of potential ideas MvC2 has both depth and breadth, and this combination makes it an intimidating game to mine. So, if MvC2 is the source we should steal from, where and how do we start? First, you must understand how to deconstruct the game, because knowing how the moves are constructed gives you a fighting game lexicon. Second, you must understand why and how you reconstruct them. Just taking random moves and smashing them — square peg round hole — into your cast of characters defeats the purpose of this exercise. Additionally, if you are making a single player action adventure game, there are certain philosophies that are incongruous with a fighting game. Your cast has roles to fulfill, so you will need to know what moves help you define these roles, how to modify these moves so they are compatible with the game you are making, and how to maintain a balance in your play.

Marvel vs Capcom 2 is an amazing resource, but it isn’t the only resource. Tekken, Street Fighter, Guilty Gear, the list goes on and on. In the next post I will talk about how to analyze, describe, and deconstruct what you are seeing in MvC2, and armed with this you will, hopefully, be able to apply this knowledge it to any game you see, not just MvC2.

The design philosophy of this game, of the VS series in general, is that if you “break” everyone, everyone is balanced.

Man I wish I had read this 3 months ago. I’ve been working on this super-smash style fighter for the 3DS and tried to keep attacks “under control” because I mistakenly thought it was the only way to make it balanced. Towards the end of the project my co-workers starting complaining that characters felt under-whelming. Soon after, I picked up MvC3 and noticed that Magneto’s disruptor was ridiculous. I couldn’t believe the developer’s left in such a broken attack, until my friend’s X factored Sentinel came back and ripped through my whole team. I ended up cutting most recovery and startup frames in half – wish I had seen this great article sooner!

Thanks, and I’m glad it could help, even if it came a little late. Design is iterative, so “better late than never”, should be a comforting mantra. Just remember that you should never “pre-balance” something, because until all the pieces are in play it is impossible to accurately judge the effects. Preemptive balancing of monsters, characters, or players is like choosing an Orchestral piece of music before knowing what instruments are even in the band. Gotta know what the pieces are, before you can make them sing in harmony.

It definitely helps. I’m excited to have stumbled on your blog – everything in here speaks to the sort of things I run into at work. Really glad to hear that other people struggle with design changes, I certainly had my moments with that “ugly baby syndrome”. Now that I’ve put a name to it and heard you describe it I can fight it off easier.

Maybe you can help with this situation I ran into at the beginning of the project. Like I mentioned, we’re making a super-smash style game and after designing all of the characters my boss asked me to design an adventure mode similar to the subspace emissary in smash bros. I remembered not particularly liking that portion of the game, so I spent a couple days playing it again and figuring out why. Afterward, we had a meeting with the department leads and producers to go over my design proposal, which highlighted potential reasons the subspace emissary wasn’t well received and how we could improve on the formula.

Health counting up and knockout deaths are really cool in the multiplayer arenas, but they cause some strange situations in platforming levels so I proposed a more traditional lives system like Mario and most other 2d platformers. There was also some other ideas about leveling up and unlocking abilities, but after considering the proposal for 2 minutes everyone voted to just copy the subspace emissary because smash sold tons of units so it must be good. Is that common, just going with what sells? We’re making the sequel so this meeting is going to come up again, got any tips?

I felt I couldn’t adequately answer you in a comment, so I wrote a new post: https://flarkminator.com/?p=312

I hope you find it helpful.

Have I been in your situation? Of course, who hasn’t. Does it bother me? Of course, why wouldn’t it. Do I let it GET to me? No, and here’s why.

My philosophy is simple. As an employee my job is two-fold: I will explain and argue my positions as eloquently and passionately as I can, and I will accept, with equal measure, my bosses eventual decisions. I argue right up until the moment a decision is made, but once it is made I let it go. You MUST let it go, or it will eat you away from the inside. There are hundreds of reasons why a decision could be swayed one way or another. I don’t know if I can give much more advice than that, other than to say there is always next time.